It came as a surprise three years ago when I started crocheting to hear people call it "knitting". Nobody who crochets or knits confuses the two, and most people who do a few textile arts can tell the difference at a glance. But a large number of people who don't do either craft haven't any idea how to distinguish them.

The sofa blanket and pillow above are both crochet. If you want to get fancy, the blanket is filet crochet. Filet crochet is a technique that uses two stitches of different sizes to create patterns, using the negative space generated by the smaller stitch for contrast.

If you see someone making fabric and are trying to tell whether it's crochet or knitting, the absolute giveaway for crochet is a hooked tool. If you aren't standing quite close enough to see whether there's a hook on the end, count the implements. One short tool is always crochet.

Crochet also holds very few stitches. If you see only one loop of yarn on the tool (or just a couple), you're looking at crochet.

Knitting uses at least two sharp ended needles with dozens of stitches all looped around the needles at the same time.

Knitting can be reproduced by machine, but crochet has to be made by hand. So everyone owns a lot of knitted items. T-shirts, socks, sweatpants, and mass produced sweaters are all knitted items. Crochet has its own distinct stitch patterns that won't look like anything in your sock drawer.

Knitting is good at creating soft stretchy fabric such as socks. Crochet tends to be stiffer so it's good for sturdy items such as placemats or tote bags. It's easier to make fancy patterns with crochet and crochet produces fabric somewhat faster than hand knitting.

Crochet is inherently denser than knitting and uses one-third more yarn to produce the same sized item. That sofa blanket in the photograph weighs about ten pounds.

----

Image credits:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Pink_knitting_in_front_of_pink_sweatshirt.JPG

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Crochet-round.jpg

Wednesday, April 14, 2010

Tuesday, April 13, 2010

Neglected subjects

This morning Peter Weis and I were chatting, and I mentioned that I was learning to use a knitting machine. He replied that Singer was famous for their knitting machines, and it was a little while before we realized that he was thinking of sewing machines rather than knitting machines. So if you've never seen a knitting machine before, this is what one looks like. Sewing machines join fabric together; knitting machines generate knitted fabric.

That red strip hanging down from the device is a piece of knitting. It curls at the side because it is a stockinette stitch (stockinette stitches like to roll and curl; that's how they behave). This knitting machine has 50 hooks threaded, half of which I'm using to produce this item. Each hook holds one stitch of fabric. The purple item at right is a shuttle, which pushes the hooks and creates knitting stitches as it moves across the hook bed. I operate this shuttle manually; higher end knitting machines can be punch card driven or computerized.

The advantage of using a knitting machine is that it can generate an entire row of stitches in the time it would take to produce two or three stitches with regular knitting needles. This device can create rows up to 100 stitches wide, and with accessory extensions I could extend that as wide as the work table.

Knitting machines aren't like regular knitting needles, though. This doesn't pack into a tote bag and carry to Starbucks. It needs a fairly large work table with specific dimensions and it has to be clamped down. It also requires engineering skill: a lot of things can go wrong with the assembly and operation.

Each knitting machine can only do certain things. The hooks are sized to a given size of yarn and spaced at a fixed spacing, which means that one machine could produce baby blankets or heavy sweaters, but not both. This flat bed knitting machine will never make socks (unless you like a seam in your socks, which nobody does--seams in socks are uncomfortable).

Before getting the flat bed machine I tried the smaller circular machine at right. It operates on a crank and generates thin rounded pieces of knitting that are suitable for cords and edging.

The smaller machine is worth getting if this intrigues you. This device doesn't work on as many types of yarn as the manufacturer claims. I've had success only with acrylics and wools in baby yarn and sock yarn. It's almost a necessity to have a lace making crochet hook in order to correct for machine errors: these devices are prone to skipping and jamming.

Although once a piece gets started properly, this is far faster than manual knitting.

In recent years basic terms and concepts in textile arts have been fading from general knowledge. These days, "needlepoint" and "knitting" and "braiding" often get misapplied to things that are not needlepoint or knitting or braiding, because a lot of people don't know enough about these subjects to tell the difference. I've created a lot of the Wikimedia Commons textile arts categories; one has to know what one is looking at to sort the content.

I uploaded these photographs to Wikimedia Commons today; they might find their way into articles soon.

That red strip hanging down from the device is a piece of knitting. It curls at the side because it is a stockinette stitch (stockinette stitches like to roll and curl; that's how they behave). This knitting machine has 50 hooks threaded, half of which I'm using to produce this item. Each hook holds one stitch of fabric. The purple item at right is a shuttle, which pushes the hooks and creates knitting stitches as it moves across the hook bed. I operate this shuttle manually; higher end knitting machines can be punch card driven or computerized.

The advantage of using a knitting machine is that it can generate an entire row of stitches in the time it would take to produce two or three stitches with regular knitting needles. This device can create rows up to 100 stitches wide, and with accessory extensions I could extend that as wide as the work table.

Knitting machines aren't like regular knitting needles, though. This doesn't pack into a tote bag and carry to Starbucks. It needs a fairly large work table with specific dimensions and it has to be clamped down. It also requires engineering skill: a lot of things can go wrong with the assembly and operation.

Each knitting machine can only do certain things. The hooks are sized to a given size of yarn and spaced at a fixed spacing, which means that one machine could produce baby blankets or heavy sweaters, but not both. This flat bed knitting machine will never make socks (unless you like a seam in your socks, which nobody does--seams in socks are uncomfortable).

Before getting the flat bed machine I tried the smaller circular machine at right. It operates on a crank and generates thin rounded pieces of knitting that are suitable for cords and edging.

The smaller machine is worth getting if this intrigues you. This device doesn't work on as many types of yarn as the manufacturer claims. I've had success only with acrylics and wools in baby yarn and sock yarn. It's almost a necessity to have a lace making crochet hook in order to correct for machine errors: these devices are prone to skipping and jamming.

Although once a piece gets started properly, this is far faster than manual knitting.

In recent years basic terms and concepts in textile arts have been fading from general knowledge. These days, "needlepoint" and "knitting" and "braiding" often get misapplied to things that are not needlepoint or knitting or braiding, because a lot of people don't know enough about these subjects to tell the difference. I've created a lot of the Wikimedia Commons textile arts categories; one has to know what one is looking at to sort the content.

I uploaded these photographs to Wikimedia Commons today; they might find their way into articles soon.

Wednesday, March 31, 2010

Wikipedia's Arbitration Committee implements genuine reform.

Good news at last: Wikipedia's Arbitration Committee has implemented a new system that saves weeks and months of hassle without any loss in quality over their previous system. Check it out here.

Saturday, March 20, 2010

Referencing comes full circle

I wonder whether amigurumi was invented to keep guys away from things. Drop an amigurumi on the remote control, send a shiver down his spine, and he leaves the room to hunt for leftover pizza while a woman settles in happily to watch the shopping channel. The cuteness factor on these things is absolutely repellent.

One of the areas where Commons and Wikipedia need more attention is textile arts. It's not as if men never touch the subject (here's a photograph of WMF volunteer coordinator Cary Bass's crochet project), but let's face it: women are underrepresented among editors and it's usually women who take an interest in the subject.

If a guy's going to work on textile arts it probably won't be amigurumi. It's a crochet form that originated in Japan to make miniature animals, such as the owl at right. I don't make them, but the quantity of amigurumi photographs at Wikimedia Commons had reached the point where a category was justified. So I made a new category today. It's the sort of housekeeping work that makes Wikimedia Commons useful and anyone can do it on subjects they happen to know.

Back at Wikipedia I added a {{Commonscat}} template at the amigurumi article to link to the new category. Then I looked at the article, which is a dreadful little stub whose only reference is an AOL blog that probably isn't reliable. So I looked for something better. Mostly the references on this type of subject aren't very good: they tend to be how-to books with a lot of patterns and minimal context. But that's better than nothing, right?

Um...

Here's an excerpt from the top return on Google Books: Amigurumi!: Super Happy Crochet Cute by Elisabeth A. Doherty

One of the areas where Commons and Wikipedia need more attention is textile arts. It's not as if men never touch the subject (here's a photograph of WMF volunteer coordinator Cary Bass's crochet project), but let's face it: women are underrepresented among editors and it's usually women who take an interest in the subject.

If a guy's going to work on textile arts it probably won't be amigurumi. It's a crochet form that originated in Japan to make miniature animals, such as the owl at right. I don't make them, but the quantity of amigurumi photographs at Wikimedia Commons had reached the point where a category was justified. So I made a new category today. It's the sort of housekeeping work that makes Wikimedia Commons useful and anyone can do it on subjects they happen to know.

Back at Wikipedia I added a {{Commonscat}} template at the amigurumi article to link to the new category. Then I looked at the article, which is a dreadful little stub whose only reference is an AOL blog that probably isn't reliable. So I looked for something better. Mostly the references on this type of subject aren't very good: they tend to be how-to books with a lot of patterns and minimal context. But that's better than nothing, right?

Um...

Here's an excerpt from the top return on Google Books: Amigurumi!: Super Happy Crochet Cute by Elisabeth A. Doherty

In Japan a crocheted or knitted doll is called an amigurumi (ah-mee-guh-ROO-mee). Disclaimer: Please, people. I do not speak Japanese. This pronunciation guide should be taken with a grain of salt. There is very little information available in English on Amigurumi, so I have decided to go with my own definition based on information I found in an online encyclopedia. Ami is a shortening of the word amimie, which means “stitch.” Gurumi is a shortening of the word nuigurumi, which means “stuffed doll or toy.” Smoosh the two together and you get amigurumi.The book was published in 2007 and that's reasonably close to Wikipedia's definition as it appeared at the end of 2006. I don't know if we'll ever get a reliable source on this stuff, but I'll keep looking.

Thursday, February 25, 2010

The good, the bad and the ugly

The following is a guest post by Peter Weis:

What is chromatic aberration?

“In optics, chromatic aberration (also called achromatism or chromatic distortion) is the failure of a lens to focus all colors to the same point”, is the first sentence in the Wikipedia entry on chromatic aberration. Basically light enters a lense in the same, aligned direction but due to the mechanical advice and its imperfection – the light leaves the lense in several unaligned directions.

We should leave the technical question at this point as well. For further information I recommend the full article.

How does that affect an image?

Chromatic aberration looks like “purple fringing”. On the image below you can see longitudial chromatic aberration. In this case all edges of your subject have purple fringes. If there are additional green fringes you speak of lateral chromatic aberration. Again for further technical information I recommend reading the article on purple fringing.

The good

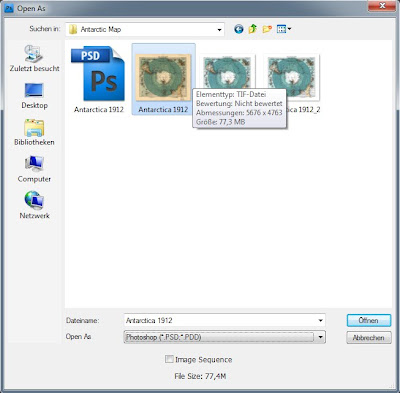

The most convenient solution for chromatic aberration is using Adobe's Camera Raw. For those amongst you who use Photoshop but never headed for Camera Raw here you go.

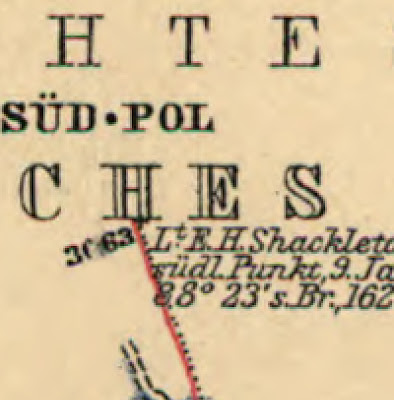

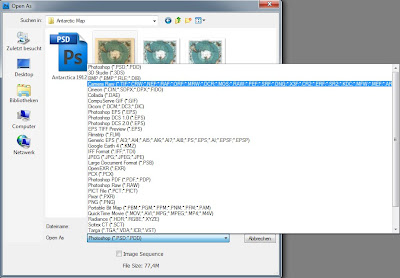

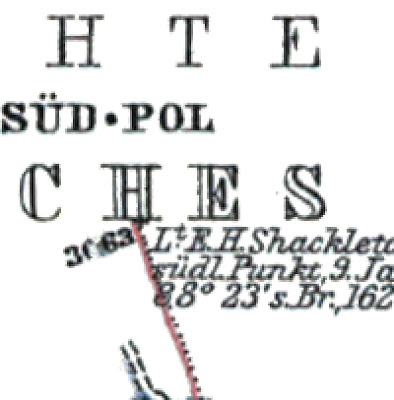

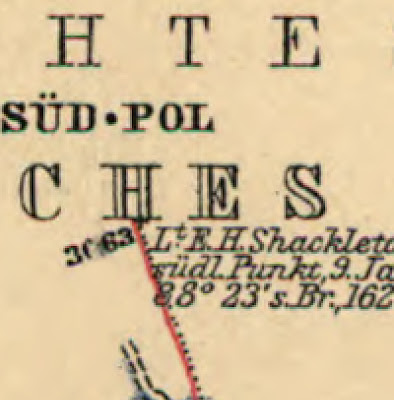

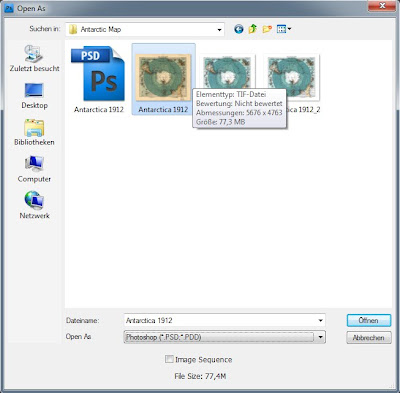

Camera Raw is freeware that enables you to work with the raw material from your DLSR. To explain the full workflow and the advantages and disadvantages of Camera Raw would be enough information for a second article – so let us focus on dealing with chromatic aberrations and purple fringing. I recently edited a map of the South Pole which had some problems.

This image was cropped at 400% - the occurring greenish/reddish fringing is between 1-3 pixels. First step is to open your Raw file with Photoshop. If Camera Raw is already installed, this should be possible by double-clicking the file.

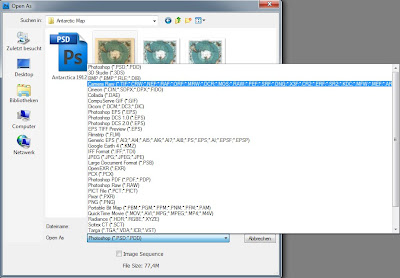

Note: If your file is not a Raw file you could nonetheless open it using Camera Raw. Here's a short how to:

Photoshop >>> File >>> Open as…

>>> [yourfile].[yourimageformat] >>>

Open as: Camera Raw

In the next step the Raw dialog should open up. The third tab from the right is “lens correction” – that’s where we will start working. The section “Chromatic Aberration” is almost self-explanatory. Depending on the colour fringing of your image you either adjust red/cyan or blue/yellow. The larger the colour fringing the easier to remove it – but don’t panic if otherwise.

In the next step the Raw dialog should open up. The third tab from the right is “lens correction” – that’s where we will start working. The section “Chromatic Aberration” is almost self-explanatory. Depending on the colour fringing of your image you either adjust red/cyan or blue/yellow. The larger the colour fringing the easier to remove it – but don’t panic if otherwise.

In this case you could use “Defringe: All Edges” or “Defringe: Hightlight Edges“. “Defringe: All Edges” will remove the colour fringing, but also results in subtle grayish lines. For my image this solution appeared to be the optimum. The defringed image tends to be a little bit desaturated, so I recommend you to slightly increase the saturation and if needed contrast. It might be helpful to have the original layer and the adjusted layer in your layers palette to directly compare what values of saturation/contrast fit the most for your project. “Defringe: Highlight Edges” is to be used if most of the colour fringing occurs in edges of highlighting, which is quite often the case. Just feel free to play around with the sliders.

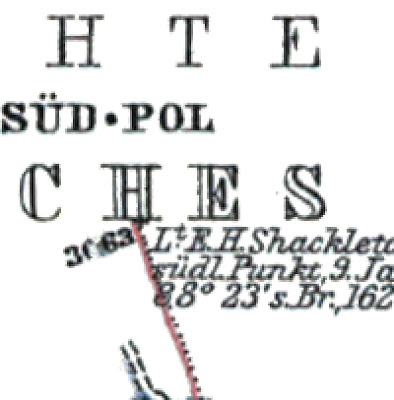

After a few hours of work including temperature, levels, curves, saturation and restoring the map the finished version looks like this:

What is chromatic aberration?

“In optics, chromatic aberration (also called achromatism or chromatic distortion) is the failure of a lens to focus all colors to the same point”, is the first sentence in the Wikipedia entry on chromatic aberration. Basically light enters a lense in the same, aligned direction but due to the mechanical advice and its imperfection – the light leaves the lense in several unaligned directions.

We should leave the technical question at this point as well. For further information I recommend the full article.

How does that affect an image?

Chromatic aberration looks like “purple fringing”. On the image below you can see longitudial chromatic aberration. In this case all edges of your subject have purple fringes. If there are additional green fringes you speak of lateral chromatic aberration. Again for further technical information I recommend reading the article on purple fringing.

The good

The most convenient solution for chromatic aberration is using Adobe's Camera Raw. For those amongst you who use Photoshop but never headed for Camera Raw here you go.

Camera Raw is freeware that enables you to work with the raw material from your DLSR. To explain the full workflow and the advantages and disadvantages of Camera Raw would be enough information for a second article – so let us focus on dealing with chromatic aberrations and purple fringing. I recently edited a map of the South Pole which had some problems.

This image was cropped at 400% - the occurring greenish/reddish fringing is between 1-3 pixels. First step is to open your Raw file with Photoshop. If Camera Raw is already installed, this should be possible by double-clicking the file.

Note: If your file is not a Raw file you could nonetheless open it using Camera Raw. Here's a short how to:

Photoshop >>> File >>> Open as…

>>> [yourfile].[yourimageformat] >>>

Open as: Camera Raw

In the next step the Raw dialog should open up. The third tab from the right is “lens correction” – that’s where we will start working. The section “Chromatic Aberration” is almost self-explanatory. Depending on the colour fringing of your image you either adjust red/cyan or blue/yellow. The larger the colour fringing the easier to remove it – but don’t panic if otherwise.

In the next step the Raw dialog should open up. The third tab from the right is “lens correction” – that’s where we will start working. The section “Chromatic Aberration” is almost self-explanatory. Depending on the colour fringing of your image you either adjust red/cyan or blue/yellow. The larger the colour fringing the easier to remove it – but don’t panic if otherwise. In this case you could use “Defringe: All Edges” or “Defringe: Hightlight Edges“. “Defringe: All Edges” will remove the colour fringing, but also results in subtle grayish lines. For my image this solution appeared to be the optimum. The defringed image tends to be a little bit desaturated, so I recommend you to slightly increase the saturation and if needed contrast. It might be helpful to have the original layer and the adjusted layer in your layers palette to directly compare what values of saturation/contrast fit the most for your project. “Defringe: Highlight Edges” is to be used if most of the colour fringing occurs in edges of highlighting, which is quite often the case. Just feel free to play around with the sliders.

After a few hours of work including temperature, levels, curves, saturation and restoring the map the finished version looks like this:

Wednesday, February 24, 2010

Writing articles for a change...and oh what a change

Strange as it may seem, I've also been known to write for Wikipedia. This last day has been more interesting than usual in that regard. You're going to love how this post ends.

Found the topic from a short mention at an administrative noticeboard.

Actual press coverage is mixed: plenty of positives, also skepticism over feasibility and hype. The company was profiled by 60 Minutes a few days ago and has been doing a media blitz since then. It's a tech firm that wants to sell green energy and is very cagey about its company secrets. They held a press conference this morning with Arnold Schwarzenegger, Colin Powell, and Michael Bloomberg. Is this pre-IPO hype?

Astroturfing jobs at Wikipedia these days are getting contracted at one or two levels of separation from the client company. So the geolocation of this major contributor is less significant than its singlemindedness. Read the edits for yourself.

http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Special:Contributions&limit=500&target=58.179.137.71

Following are a few highlights from the IP's attempts to reinsert promotional content into company history such as a tangential NASA connection that the CEO had prior to founding the startup:

*(the idea came from somewhere....look at the Microsoft Page....)

*(one fine day in 2001, Mr Sridhar became an expert in fuel cells!)

*(the fucking Google page says where the name Google came from!!!!! ok, bitch?)

The last of those comments looks to have been intended toward me; the IP user appears not to have noticed that by this time the IP was actually edit warring with a male administrator. This IP editor doesn't seem to understand much about the underlying engineering or science. At one point I stopped to explain that hydrolysis consumes energy rather than produces it; shortly afterward the IP shuffled sentences so it looked like a venture capitalist was using a cost per kilowatt hour argument to rebut a criticism about fuel cell manufacturing costs.

The firm has $400 million in venture capital and a burn rate of $85 million a year. Everyone loves green energy--or would if it were cost effective--but this looks like a very high stakes gamble. Bloom Energy's business plan is based upon a bet that a notoriously unstable technology can be mass produced by a startup firm headed by a Ph.D. who never got any closer to NASA than managing a university department that built prototypes. Instead of Schwarzenegger and Powell, I wish that company had introduced its VP of production at the press conference today.

It turns out that Sprint Nextel owns 15 patents on similar fuel cell technology and has been using their own models in the field for five years. The Department of Energy gave Sprint a $7 million grant last year to expand their program. Quite a few other firms are active in the area. It isn't clear what Bloom Energy has that they don't--other than a star studded board and a hype generator. It could be the start of a new era or it could be the next Pets.com.

Among the interesting tidbits I found was a piece from Wired that had located a 2009 patent award to Bloom Energy for a device that seems very similar to its Bloom Energy Server. Perhaps the vaunted "secret ingredient". Did you know...

Time to go back onsite and politely congratulate that IP coauthor. Entries at Wikipedia's "Did you know?" feature remain live about six hours. Wikipedia's main page typically receives 1 million page views during that time.

Found the topic from a short mention at an administrative noticeboard.

It appears that this article on a California company may be part of that company's pre-IPO publicity blitz. The company's website, linked from the article, shows a countdown clock for tomorrow at 9:00 am local time. Given that just a few contributors wrote most of the article over the past few days, is this cause for concern? User:LeadSongDog come howl 21:37, 23 February 2010 (UTC)The good thing about blogging is it gives the chance to be more candid. So not to mince words, this looked like astroturfing. Here's how it appeared shortly before my first edit. Red flags for promotional writing include awards in the lead and a single sentence of criticism backloaded at the tail end of the article. The section entitled "Competition" used one source that basically stated the major players had recently pulled out of the field. If you check the references the quotes turn out to be cherry picked.

Actual press coverage is mixed: plenty of positives, also skepticism over feasibility and hype. The company was profiled by 60 Minutes a few days ago and has been doing a media blitz since then. It's a tech firm that wants to sell green energy and is very cagey about its company secrets. They held a press conference this morning with Arnold Schwarzenegger, Colin Powell, and Michael Bloomberg. Is this pre-IPO hype?

Astroturfing jobs at Wikipedia these days are getting contracted at one or two levels of separation from the client company. So the geolocation of this major contributor is less significant than its singlemindedness. Read the edits for yourself.

http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Special:Contributions&limit=500&target=58.179.137.71

Following are a few highlights from the IP's attempts to reinsert promotional content into company history such as a tangential NASA connection that the CEO had prior to founding the startup:

*(the idea came from somewhere....look at the Microsoft Page....)

*(one fine day in 2001, Mr Sridhar became an expert in fuel cells!)

*(the fucking Google page says where the name Google came from!!!!! ok, bitch?)

The last of those comments looks to have been intended toward me; the IP user appears not to have noticed that by this time the IP was actually edit warring with a male administrator. This IP editor doesn't seem to understand much about the underlying engineering or science. At one point I stopped to explain that hydrolysis consumes energy rather than produces it; shortly afterward the IP shuffled sentences so it looked like a venture capitalist was using a cost per kilowatt hour argument to rebut a criticism about fuel cell manufacturing costs.

The firm has $400 million in venture capital and a burn rate of $85 million a year. Everyone loves green energy--or would if it were cost effective--but this looks like a very high stakes gamble. Bloom Energy's business plan is based upon a bet that a notoriously unstable technology can be mass produced by a startup firm headed by a Ph.D. who never got any closer to NASA than managing a university department that built prototypes. Instead of Schwarzenegger and Powell, I wish that company had introduced its VP of production at the press conference today.

It turns out that Sprint Nextel owns 15 patents on similar fuel cell technology and has been using their own models in the field for five years. The Department of Energy gave Sprint a $7 million grant last year to expand their program. Quite a few other firms are active in the area. It isn't clear what Bloom Energy has that they don't--other than a star studded board and a hype generator. It could be the start of a new era or it could be the next Pets.com.

Among the interesting tidbits I found was a piece from Wired that had located a 2009 patent award to Bloom Energy for a device that seems very similar to its Bloom Energy Server. Perhaps the vaunted "secret ingredient". Did you know...

... that Bloom Energy was awarded a patent in 2009 for a power device that utilizes yttria-stabilized zirconia?That lovely bit of information is on Wikipedia's main page right now.

Time to go back onsite and politely congratulate that IP coauthor. Entries at Wikipedia's "Did you know?" feature remain live about six hours. Wikipedia's main page typically receives 1 million page views during that time.

Saturday, February 06, 2010

Lead room

One factor to consider when cropping a portrait is lead room. When a subject looks to one side viewers become curious where the person is looking. Lead room adds a sense of meaning to facial expressions and gives compositions a satisfactory emotional balance. This 1935 portrait has a beautiful use of lead room: it was taken by photographer Ben Shahn in Jackson Square, New Orleans. A wide space to the left enhances the wistful expression in the subject's eyes.

To see what a difference the lead room makes, let's try cropping out part of the photograph so he looks centered. The effect isn't nearly so pleasing.

To see what a difference the lead room makes, let's try cropping out part of the photograph so he looks centered. The effect isn't nearly so pleasing.

Human beings take cues from the eyes of other people. We want to know what catches their attention; there's an urge to glance in the same direction. Even when we know that we're looking at a very old portrait we feel that urge; it's instinctive. And although this subject's expression is exactly the same the cropped version seems caged; we glean less from it. The slouch and the knitted brow don't convey as much.

Last night the concept of lead room intruded on a search for historic Irish portraits that Alison and I were doing. She wanted Countess Markiewicz and we found a 12 MB portrait that was feasible but not ideal.

This doesn't have Ben Shahn's artistry and the lead room is on the wrong side. Plus the image has more damage at right than at left. There isn't much room to crop in any direction and the crop I want to make out of sheer laziness would get rid of that bright vertical band. But then we would lose precious lead room and this photograph doesn't have enough of it anyway.

It only takes a moment to perform a crop, but the decisions that go into it mean a great deal. Historic material sometimes carries unavoidable flaws. Alison was willing to work with this anyway; Countess Markiewicz was the first woman in Europe to hold a cabinet minister position in a national government; she was Minister of Labor for Ireland from 1919-1922 (Alison might want to throttle me for not spelling that L-a-b-o-u-r but I'm an ignorant Yank).

She's doing most of the work herself. I offered to crop. There's no really good choice here and a lot of bad ones.

I wanted to crop away at left to balance the lead room but couldn't really go very far: her long skirt, the andirons, her fingers, and the books on the mantel all got in the way. So I left a lot of the bright vertical band at far right. It's a correctable problem. Alison will need extra work to fix it--and somehow I suspect I may be helping with those touches. But the result will be worth it.

For comparison here's a "lazy editor's crop" alternate. Less work to restore but it would never be as good.

So cheers to Alison! (And now, since I'm such an evil wiki witch, she'll just have to do this restoration so you can all read the followup. Excuse me while I drop another newt into the cauldron...)

Friday, February 05, 2010

Copyright limbo

Today's example of Sigmund Freud isn't so much an example as a contemplation of copyright law. The portrait was taken in 1914, which makes it public domain under United States law. If the portrait had been taken ten years later then Wikimedia Commons wouldn't be able to host it. Although all of Freud's writings entered public domain in the European Union at the start of 2010, United States law doesn't recognize all of his work as public domain. It's a really weird quirk that causes big obstacles.

Copyright terms in the European Union run for the life of the author plus seventy years. Freud died in 1939. So on January 1 2010 all of his copyrights expired in Austria and the United Kingdom. Most countries reflect that lapse in their own law by a provision known as the rule of the shorter term, but the United States doesn't follow the rule of the shorter term.

So I could republish all of Freud's writings from Vienna where they're public domain, but not from the US where they remain under copyright. The Wikimedia Foundation servers are located in the United States. So because the servers fall under United States law, Austrian Wikimedians can't bring Freud's later writings onto the German language Wikisource (which hosts free licensed texts).

United States copyright law is complex, but one rule that holds true nearly all of the time in the States is that material which was published before 1923 is public domain (no matter when the author died). So this 1914 portrait is fine to reuse but a 1924 portrait wouldn't necessarily be free. That copyright gap is going to widen: Anne Frank's autobiography will lapse into public domain in The Netherlands in 2015 but will remain under copyright in the United States. Broadly speaking, United States copyrights are in a holding pattern until 2020. So 1923 works won't lapse public domain for at least another ten years.

For the last thirty years U.S. copyright law has been getting a series of extensions. Those extensions have something to do with lobbying by the Walt Disney Corporation: Mickey Mouse was created in 1925. It doesn't actually protect the value of Mickey Mouse to keep Sigmund Freud under copyright in the United States, though. The United States could adopt the rule of the shorter term without harming Disney's profits.

Other culturally valuable material is getting tied up because of this legal hitch: William Butler Yeats's works entered public domain in his native country of Ireland this year. I can republish this 1911 portrait of him freely, but I can't republish his late poems.

And one thing worth wondering is this: with a normal copyrighted work it could be possible to contact the copyright owner and request a release under copyleft license. How does one seek access to material that remains under a copyright which no one seems to own?

Copyright terms in the European Union run for the life of the author plus seventy years. Freud died in 1939. So on January 1 2010 all of his copyrights expired in Austria and the United Kingdom. Most countries reflect that lapse in their own law by a provision known as the rule of the shorter term, but the United States doesn't follow the rule of the shorter term.

So I could republish all of Freud's writings from Vienna where they're public domain, but not from the US where they remain under copyright. The Wikimedia Foundation servers are located in the United States. So because the servers fall under United States law, Austrian Wikimedians can't bring Freud's later writings onto the German language Wikisource (which hosts free licensed texts).

United States copyright law is complex, but one rule that holds true nearly all of the time in the States is that material which was published before 1923 is public domain (no matter when the author died). So this 1914 portrait is fine to reuse but a 1924 portrait wouldn't necessarily be free. That copyright gap is going to widen: Anne Frank's autobiography will lapse into public domain in The Netherlands in 2015 but will remain under copyright in the United States. Broadly speaking, United States copyrights are in a holding pattern until 2020. So 1923 works won't lapse public domain for at least another ten years.

For the last thirty years U.S. copyright law has been getting a series of extensions. Those extensions have something to do with lobbying by the Walt Disney Corporation: Mickey Mouse was created in 1925. It doesn't actually protect the value of Mickey Mouse to keep Sigmund Freud under copyright in the United States, though. The United States could adopt the rule of the shorter term without harming Disney's profits.

And one thing worth wondering is this: with a normal copyrighted work it could be possible to contact the copyright owner and request a release under copyleft license. How does one seek access to material that remains under a copyright which no one seems to own?

Labels:

copyleft,

free culture,

rule of the shorter term

Wednesday, February 03, 2010

More than one way to skin a cat

Last month I posted about restoration work on a portrait of opera singer Jenny Lind. Today I came across another graphic artist's approach to restoring her portrait. It's an interesting peek at how different two approaches can be. Robert C. McLaughlin's restoration is a composite of two different photographs including the one from the Library of Congress that I've been using.

He specifically avoids using the healing brush and works toward a much more artistic effect. The result looks more like a pencil sketch than a photograph.

He specifically avoids using the healing brush and works toward a much more artistic effect. The result looks more like a pencil sketch than a photograph.

Sunday, January 31, 2010

The fast food hamburger of digital editing

Today I'm going to do the unspeakable: praise the Photoshop auto levels function. This is something like a fine chef admitting to liking fast food. Auto levels is notorious as the one click tool that gives mediocre results. It's reliable, quick, easy, and not very good for you. Sort of like a hamburger. And yes, I have a use for it. Not the usual use, though.

NativeForeigner is working on another Crimean War lithograph. He asked me to check his progress, which was very good except for something he hadn't noticed yet. A problem loomed in the upper left corner.

NativeForeigner is working on another Crimean War lithograph. He asked me to check his progress, which was very good except for something he hadn't noticed yet. A problem loomed in the upper left corner.

Don't see it yet? Neither did Native Foreigner. And neither would I unless I had worked with this type of image before. Now let's peek at what the auto levels function reveals: big stains!

A lot of nineteenth century lithographs have subtle problems with vertical banding that show up in the sky. I suspect this is because they had been rolled for storage at some point. This type of problem tends to seem very faint until the editor adjusts the histogram. And then there's just no ignoring it.

If I suspect an image might have this type of problem I preview it in auto levels to gauge the severity.

And to all the other digital image editors who are gasping at this statement, please remember:

That's preview.

pre-view

p-r-e-v-i-e-w.

Please don't pounce on me like you're all chefs who've just caught a fellow chef munching French fries.

Using the History option we step back from that auto levels version. It's too early to really change the histogram permanently. That preview gave a very clear look at the side, shape, and darkness of the staining problem. Now we're going to resolve the problem. There are different ways to do this. A lot of people like the Dodge and Burn tools. I prefer masks and brightness adjustments.

The way I solve this is to draw a free form selection and add feathering. Feathering a selection blends its borders. This edit used 10 pixels of feathering and increased the brightness by 2 in the selected area. If you like to be cautious you can do these edits within new layers. Then redraw another selection, make a very slight adjustment, and keep going until the stains vanish.

Here's the effect of the first edit in another levels preview. Once NativeForeigner understood this he did the remaining work himself.

Saturday, January 30, 2010

Library of Congress starts open source initiative

Considering how much of the historic media at Wikipedia comes from the Library of Congress, it may surprise you that the Wikimedia Foundation has no formal partnership with the Library of Congress.

Yesterday Slashdot picked up on a Library of Congress initiative to do more of their work with open source software. It would make a lot of sense if the Library of Congress interfaced directly with the world's most successful open source nonprofit: Wikimedia. The Library of Congress has been absolutely wonderful about making its material available to the public at high resolution. Today's post expresses appreciation for that openness in the hope that this valuable synergy will be appreciated and built upon.

Eight of the images that ran on the main page of the English Wikipedia this month came from the Library of Congress collection. The image above is a landscape of Havana, Cuba painted in 1639 by Johannes Vingboons, which I restored. Wikipedia's main page received 4.0 million page views while it ran at the Picture of the Day feature on January 1, 2010. The image itself received 11,900 direct page views that day and a total of 13,382 direct views this month. All of the page view statistics for Wikipedia's main page are confirmed here.

Altogether that totals 41.1 million page views this month for Wikipedia's main page while media from the Library of Congress was running on it, and 161,468 direct page views for the eight Library of Congress images that were highlighted as Picture of the Day. These numbers are typical for the attention the Library of Congress collection is receiving through Wikimedian volunteer efforts.

I'd like to coordinate directly with the Library of Congress management to utilize this synergy better. And if the Library of Congress isn't interested I'll be happy to work more closely with institutions such as the Tropenmuseum that see the potential.

Yesterday Slashdot picked up on a Library of Congress initiative to do more of their work with open source software. It would make a lot of sense if the Library of Congress interfaced directly with the world's most successful open source nonprofit: Wikimedia. The Library of Congress has been absolutely wonderful about making its material available to the public at high resolution. Today's post expresses appreciation for that openness in the hope that this valuable synergy will be appreciated and built upon.

Eight of the images that ran on the main page of the English Wikipedia this month came from the Library of Congress collection. The image above is a landscape of Havana, Cuba painted in 1639 by Johannes Vingboons, which I restored. Wikipedia's main page received 4.0 million page views while it ran at the Picture of the Day feature on January 1, 2010. The image itself received 11,900 direct page views that day and a total of 13,382 direct views this month. All of the page view statistics for Wikipedia's main page are confirmed here.

The Picture of the Day for January 6, 2010 was a seventeenth century chiaroscuro woodcut by Bartolommeo Coriolano, who was knighted by Pope Urban VII for his artistic work in engravings and woodcuts. I did the restoration. Wikipedia's main page received 5.1 million page views on January 6 and the image itself received 7937 direct page views this month.

This 1868 portrait of an Argentine gaucho was Picture of the Day on January 8. Wikipedia's main page received 5.2 million page views that day and the image received 16,427 direct views this month. This was another of my restorations. We'll be seeing other volunteers' work too.

This 1890s photochrom print of the quays at Waterford, Ireland was restored by Jake Wartenberg. It was Picture of the Day on January 14 when Wikipedia's main page received 5.3 million page views. Jake's restoration has received 33,629 direct page views so far this month. Good work, Jake!

The artist for this woodblock print of a women's bathhouse was Torii Kiyonaga, 1752-1815. Wikipedian editor Torsodog performed the restoration. It was Picture of the Day on January 18 when Wikipedia's main page received 5.6 million page views. The image has received 39,158 direct page views this month.

On January 20 Wikipedia's main page ran this albumen print of Moroccan snake charmers, which was created during the latter half of the nineteenth century. This was another of my restorations. Wikipedia's main page received 5.3 million page views that day. The image file has received 17,884 direct views this month.

On January 21 another one of Jake Wartenberg's restorations ran on Wikipedia's main page. This is an 1856 lithograph of the hospital at Selimiye Barracks where Florence Nightingale worked during the Crimean War. The main page had 5.3 million page views on January 21 and the image file received 21,840 direct views this month.

This theatrical advertisement from 1900 was restored by Adam Cuerden. While it was Wikipedia's Picture of the Day for January 22, the site's main page received 5.3 million page views. The image file hosting page has received 11,211 direct views this month.

Altogether that totals 41.1 million page views this month for Wikipedia's main page while media from the Library of Congress was running on it, and 161,468 direct page views for the eight Library of Congress images that were highlighted as Picture of the Day. These numbers are typical for the attention the Library of Congress collection is receiving through Wikimedian volunteer efforts.

I'd like to coordinate directly with the Library of Congress management to utilize this synergy better. And if the Library of Congress isn't interested I'll be happy to work more closely with institutions such as the Tropenmuseum that see the potential.

Friday, January 29, 2010

SMS Moltke

Staxringold asked me to collaborate with him on this restoration of the SMS Moltke at Hampton Roads, Virginia in 1912. There was a difficult repair in the foreground on this image, which was 147 MB at full resolution in uncompressed TIFF format. At preview size the area looks like two white marks in the waves about two-thirds of the way to the left.

Staxringold asked me to collaborate with him on this restoration of the SMS Moltke at Hampton Roads, Virginia in 1912. There was a difficult repair in the foreground on this image, which was 147 MB at full resolution in uncompressed TIFF format. At preview size the area looks like two white marks in the waves about two-thirds of the way to the left.This image was digitized from a glass plate negative. Glass plate photography was developed in the mid-nineteenth century and was widely used until the early decades of the twentieth century when photographic film was introduced.

One of the problems with this format, though, is that the photographic emulsion is prone to damage. Once damage occurs the emulsion can peel away from the glass. That's starting to happen in this section. The challenge I faced was to reconstruct the appearance of choppy water. The sequence you'll see below was the progressive work on this area that I showed to Staxringold so he can do this type of area himself next time. The following sections are screen shots at 200% resolution.

If it seems a little nutty to work at 200% resolution on a 147 MB digitization of a negative that was no larger than 5" x 7", maybe it is. But glass plates are a high resolution format. Film gained dominance in the consumer market because it was less fragile and easier to work with. Glass plates remained in use for technical purposes such as astronomy and medical imaging until digital technologies took over at the very end of the twentieth century.

All in all, that makes a pretty good useful lifespan for a technology that came into wide use during the American Civil War.

All in all, that makes a pretty good useful lifespan for a technology that came into wide use during the American Civil War.

Thursday, January 28, 2010

D-Day

Occasionally digital restoration raises new questions. This photograph depicts a synagogue in New York City on D-Day, 1944. The Library of Congress didn't identify which congregation. A Wikipedian who edits under the username Pharos has identified it as Congregation Emunath Israel on West Twenty-third Street.

I've requested this to be Wikipedia's picture of the day for June 6, 2010.

It would be really wonderful to make contact with this congregation before that day so they know about it. A few of their older members might even be able to name who these women are. Unfortunately they don't have a website or publish an email address. Their telephone goes directly into a voice mail system.

So if you live in New York City or know a friend who does, would you be willing to help contact this congregation please? I'd really appreciate the help.

Wednesday, January 27, 2010

This stinks in Cologne

The fourth largest city in Germany actually is quite beautiful. The photograph here was taken by a German Wikimedian named Thomas Wolf and it is featured in three languages. The thing that stinks is that the city's archive building collapsed last year; Cologne's archive had been one of the very few that had survived World War II completely intact. Last March the city was constructing a subway on the same street. Then suddenly the archive tumbled.

Two people died. Thousands of documents going back nearly 1100 years were in rubble. Half a million photographs were housed there. Disasters such as the Cologne archive collapse demonstrate why it is important to digitize cultural records. Digital versions help protect and preserve a heritage.

So with thoughts of Cologne, here's a photochrom print circa 1910 of the Eisenbahn Bridge at Cologne from the Library of Congress collection. I haven't restored it yet; maybe someday.

Two people died. Thousands of documents going back nearly 1100 years were in rubble. Half a million photographs were housed there. Disasters such as the Cologne archive collapse demonstrate why it is important to digitize cultural records. Digital versions help protect and preserve a heritage.

So with thoughts of Cologne, here's a photochrom print circa 1910 of the Eisenbahn Bridge at Cologne from the Library of Congress collection. I haven't restored it yet; maybe someday.

Tuesday, January 26, 2010

Looking ahead

Congratulations to Coffee on his first digitally restored featured picture: a nineteenth century whiskey advertisement so politically incorrect it's almost quaint. It really is wonderful and rewarding to help new people such as NativeForeigner and Coffee learn digital restoration. Yet tutoring is very time consuming.

So today's post is brief: it's time to scale up this digital restoration work. One way to do that is to collaborate with art schools. What I'd like to do is get this incorporated into the curricula of advanced digital editing classes with the best student work to be selected for exhibition in museums. We have the contacts on the museum side to make that happen.

If you have contacts with an art school, please put them in touch with me: nadezhda(dot)durova(at)gmail(dot)com

So today's post is brief: it's time to scale up this digital restoration work. One way to do that is to collaborate with art schools. What I'd like to do is get this incorporated into the curricula of advanced digital editing classes with the best student work to be selected for exhibition in museums. We have the contacts on the museum side to make that happen.

If you have contacts with an art school, please put them in touch with me: nadezhda(dot)durova(at)gmail(dot)com

Monday, January 25, 2010

Beginner's luck

Would you believe that this image is not only an editor's first restoration, but his first digital editing project of any sort? NativeForeigner asked me to help choose his first project a few days ago. After discussing several options I pointed him to a series of lithographs about the Crimean War. The Library of Congress owns a wonderful set created by William Simpson in the mid-1850s that's been well preserved. He installed GIMP and Skype, we traded screen shots and shared ideas, and he performed most of the edits himself. Here's a view of the unedited original.

NativeForeigner trusted my advice and did the first three passes himself. He only really needed to pause for advice again to address a stain at the lower left corner: a dark spot surrounded by a fainter orange mark. He corrected that problem with clone stamping.

NativeForeigner trusted my advice and did the first three passes himself. He only really needed to pause for advice again to address a stain at the lower left corner: a dark spot surrounded by a fainter orange mark. He corrected that problem with clone stamping.

NativeForeigner inspired me to think of this when he showed an interest in Roger Fenton's Crimean War photography. The Simpson lithographs make wonderful beginner projects.

So today we'll share a few highlights from the collaboration. NativeForeigner's first question was how to address the area in this screen shot.

How many of these marks are intentional, he wondered? I sent back a draft edit of a suggested first pass to the section. The key concept here is that it's easier to take away than to readd data. So when something is uncertain, leave it for later and work on the easier material while you grow more familiar with the image and gain an understanding of its context.

NativeForeigner trusted my advice and did the first three passes himself. He only really needed to pause for advice again to address a stain at the lower left corner: a dark spot surrounded by a fainter orange mark. He corrected that problem with clone stamping.

NativeForeigner trusted my advice and did the first three passes himself. He only really needed to pause for advice again to address a stain at the lower left corner: a dark spot surrounded by a fainter orange mark. He corrected that problem with clone stamping.After his third pass I found a damaged portion in the sky at upper right, which he corrected. Then he transferred the file and I gave the image a pass to correct for scratches, creases, and subtle stains. Then a Curves adjustment and a color balance provided the final touches.

We're creating the featured picture nomination together at Wikimedia Commons as I write this post. Once it goes live we'll add the image to articles on Wikipedia. This illustration, which was published in April 1855, shows the conditions that Florence Nightingale confronted when she arrived at Balaklava in late 1854. Her work to improve care for the wounded and sick during that war established her reputation. In many ways that turned nursing into a modern and respected profession.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)